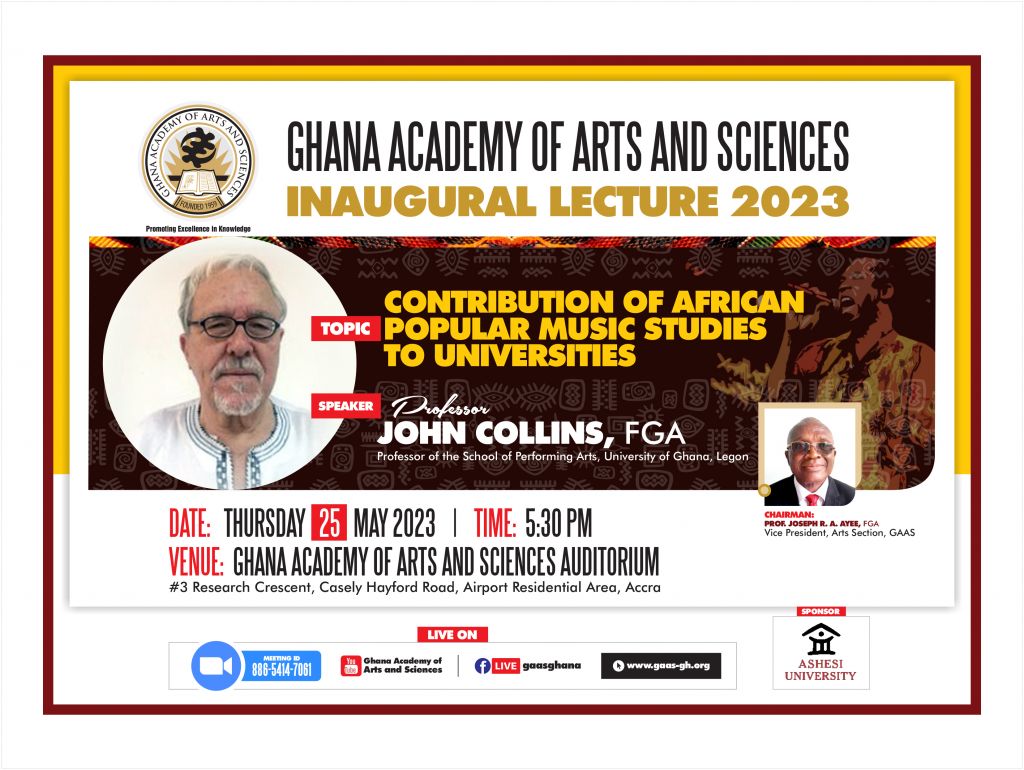

Speaker – Professor John Collins

John Collins has been active in the Ghanaian/West African music scene since 1969 as a guitarist, band leader, music union activist, journalist, writer, scholar and archivist. He obtained his B.A. degree in Sociology and Archaeology from the University of Ghana in 1972 and his Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology from SUNY Buffalo in 1994. Collins has given many radio and television broadcasts, including 40 for the BBC, and has been a consultant for numerous films on African music. In the 1980s he operated his Bokoor Recording Studio at South Ofankor. During the 1990s Collins was Technical Director of the University of Ghana and University of Mainz music digital re-documentation project, and for seven years was a Trustee of the Ghana National Folklore Board

Collins began teaching at the Music Department of the University of Ghana in 1995, obtained a Full Professorship there in 2002 and between 2003-5 was Head of Department. He also co-ran the university based Local Dimension band, and in the early 2000s worked as a consultant for World Bank programs assisting the African music industry. Collins naturalised as a Ghanaian in 2008. He is currently on post-retirement contract with the university, is a patron of the Ghana Musicians Union MUSIGA, is Chairman of the BAPMAF African Popular Music Archives, and became a member of this Academy in 2020.

Collins has around 100 published articles and books on African music and is a member of the Ghana Association of Writers. He is currently teaching a New York University in Ghana course on contemporary African music, and is also on the Highlife Music Committee of the National Folklore Board that is working on listing Highlife as a UNESCO World Intangible Cultural Heritage

Synopsis of Lecture

This presentation concerns the importance of African popular music studies for Ghanaian University departments. It begins with the difficulties in getting this topic accepted into Academia despite the fact that Kwame Nkrumah fully endorsed the popular performance sector, as well as traditional music and African art-music as part of Ghana’s national culture development plan. Because of his overthrow in 1966 his well-rounded tripartite approach to national culture (i.e., traditional, art and popular music) was not fully transmitted into the university curriculum which for many years did not include any classes on African popular music, including even on Ghana’s homegrown highlife. Indeed, the first African popular music courses were only introduced to the University Music Department students in the late 1990s, beginning first at Legon by myself and Professor Willie Anku. So this presentation begins with the benefits these new courses brought to the Music Department and School of Performing Arts: namely training students to play highlife, providing pedagogic teaching materials from the scores of local popular music, supplying knowledge and skills to help students find jobs in the booming popular entertainments and creative industries sector, being a course attractive to foreign students, and establishing Music Department bands that showcase highlife and other forms of African popular music. The presentation then turns to six non-performance university departments that benefit from African popular music studies

[ONE] HISTORY DEPARTMENTS: Popular music was a product of the urban masses, rural poor and semi-literates, and so its texts are a source of historical information on their views and aspirations. This is known as the ‘History of the Inarticulate’ approach that counters orthodox histories that are usually written by and from the point of view of the powerful and educated elites. The text of highlife available on records pressed since the late 1920s rather provides historians with running socio-historical commentaries on and vernacular critiques of westernisation by colonised and subaltern peoples.

[TWO] SOCIOLOGY DEPTS: African popular music provides a trans-ethnic artistic linguafranca suitable for polyglot African city dwellers and its text reflects the positive and negative effects of rapid urbanization: such as urban pull and new fashions, urban migration, the break-up of the extended family and the associated themes of ‘abusua bone’ and the orphan child. Moreover, highlife/African popular music reflects the views of the various urban youth sub-cultures that have emerged in Ghana since the mid-1900s that range from the 1960s ‘Tokyo Joes’ and rock ‘n’ roll generation to the ‘Afro’ and psychedelic fashions of local 1970s ‘soul brothers’ to the hooded ‘yo-yo boys’ of today’s hiplife

[THREE] POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPTS: Popular artists supported the independence struggle and as highlife is transethnic it helped during the early independence era forge a national and even Pan-African identity (cf. ‘tribal’ one). Nkrumah thus used highlife artists as cultural ambassadors and for propaganda purposes. More recently, highlife and other forms of African popular music have provided platforms for protest against various post-independence governments and regimes, examples being Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat that supports the down-trodden Nigerian ‘suffer heads’, and the African Brothers 1967 highlife ‘Ebi tie ye’ that couches the rise of the nouveau riche in Akan animal parable form. African popular music studies, therefore, demonstrate the contribution of the low-status popular performers to modern African political identity and discourse,

[FOUR] AFRICAN/BLACK STUDIES DEPTS: Because Black American popular performance contains African ingredients whilst highlife and other forms of African popular music include a substantial Black American component, African popular music studies throw light on the long-term transatlantic cultural dialogue between Africa and the Black Americas. This two-way ‘Black Atlantic’ relationship began when slaves were taken to the Americas, and then from the 19th century continued in the opposite direction through the cultural and artistic impact of the Black Diaspora on Africa. Professor Atta Annan Mensah calls this a musical ‘Homecoming’ whilst I call it a ‘Black Trans-Atlantic Cultural Feedback’; with the earliest examples taking place in the 19th century when Jamaican ‘maroon’ freed slaves introduced gumbay music to West Africa and Black Caribbean soldiers introduced calypsos. These genres both fed into emerging African popular music: followed later by influences coming from jazz, sambas, rumbas, soul, funk, R&B, reggae – and today hip-hop and dancehall.

[FIVE] GENDER STUDIES DEPTS: African popular music recordings that go back to the 1930s can be used to examine the changing attitudes of society to the role and status of women. The female point of view was added in the 1950s when women began to become significant African famous music artists: like South Africa’s Miriam Makeba and Ghana’s Julie Okine. In fact, in 2008-9 the University of Ghana’s Centre for Gender Studies and Advocacy (CEGENSA) used this recording source of information for its ‘Changing Representations of Women in Popular Music’ project for which I supplied 300 Ghanaian popular songs from the 1930s-present that touched on gender issues.

[SIX] DEVELOPMENTAL STUDIES DEPTS: Because African traditional and urban popular performance styles have co-existed side-by-side for well over a century these genres have interacted with one another, with local popular music drawing on indigenous resources, and local popular music, in turn, influencing traditional music-making; leading to neo-traditional drum-dance styles such as the simpa, borborbor and kpanlogo of Ghana. So, for African/Ghanaian performance, the relationship between the popular and traditional, the old and new and the rural and urban, is circular and reciprocal. This looped cultural dynamic, therefore, questions simplistic linear ‘Euro-centric’ developmental theories of African social-cultural change that presume that there is only a single straight-line path from tradition to modernity, treats tradition and modernity as inherently antagonistic and assumes that African customs must be replaced as they put a restraining brake on development.

View programme brochure online

Download the programme brochure in PDF

Watch the Lecture online